Continuing the story based on a fictional character Steve Wallace who in the late 1970s works in the Solomon Islands. This is the second part.

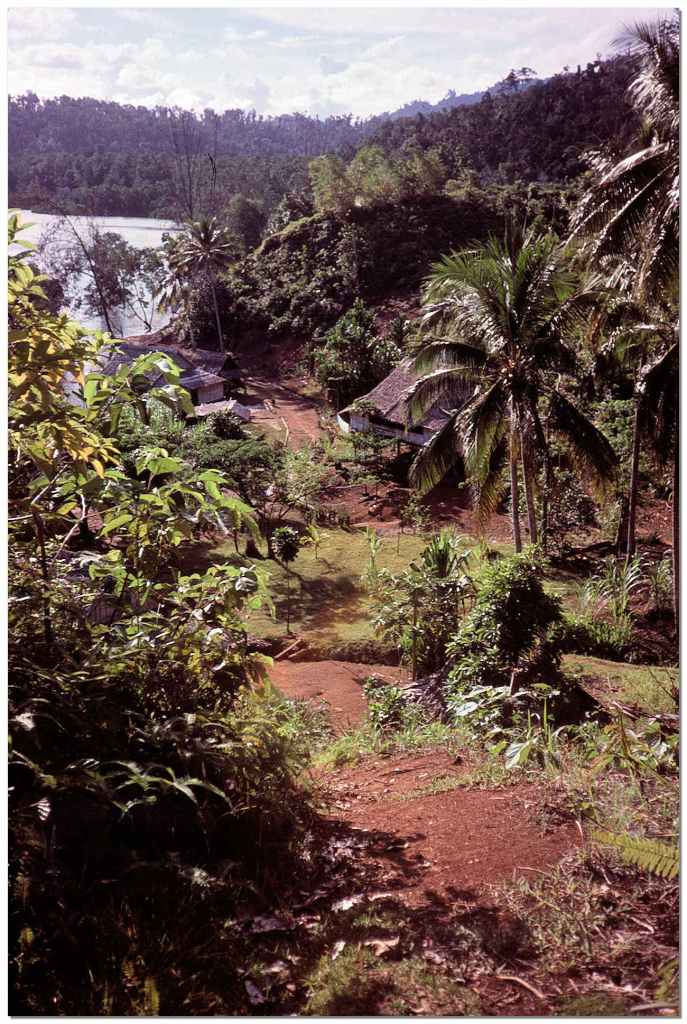

Steve arrived by canoe on Tanabuli island four days ago. The village of about twenty houses is located on the landward side of the small island. After a morning surveying for a water source with Moses, he now waits for transport back to Buala.

The Tanabuli water supply, one of the simplest, will be a corrugated roof and a storage tank. It is one of a number coordinated and managed by Steve, alongside training his local replacement. To his great frustration he has no budget for transport so his travel arrangements are ad hoc. His Buala base is about 30 miles along the cost to the north where a small contingent of Solomon Islanders work as civil servants. He is the only white man there, living in the “Doctors” house, that is until there is funding for a doctor.

Yesterday a boat came by, the MV Ligomo, the sound of its diesel engine carrying miles across the water before it came in sight. It was going south to Honiara, the wrong direction for Steve. Anchoring just offshore it was quickly circled by children in canoes, shouting back and forth with the fifteen or so passengers. A villager loaded some bags of copra and left with them for the capital.

The Ligomo would be back in four or five days, or maybe seven or eight, depending on which way it circles the island on its return, there will be a message on the radio. Steve hopes he is long gone before then; maybe a plantation boat or a canoe from the Malaria Control Team, who have given him many a ride.

During the morning he sits on the split cane floor reviewing his field notes, reading or playing cards. In the late morning he has a short swim and returns to doze in the heavy oppressive heat. Patience, patience, patience, he tells himself, my yoga mantra.

The village is quiet. Now and again he hears distant shouts and whoops from islanders in their gardens on the hills across the bay, and sees smoke rising from their fires.

After midday Steve hears a canoe arriving. Silas, a villager comes to tell him he is taking the Santa Isabel Bishop, back to his Buala home next morning; he thinks Steve should get a lift with him and his family. Silas and Steve will leave first thing to pick them up from a nearby village.

“That’s great! At last! I met the Bishop at the Sepi festival last year.” Steve says suppressing excitement. Silas leaves a pineapple and a parcel of cassava and returns to his canoe.

In the afternoon as the intense midday heat has waned, Moses arrives to take him fishing. They paddle away from the village, into turquoise waters on the seaward side of the island. There is a little swell, no wind and in about 10-foot of water Moses drops anchor. With goggles and a hand slung catapult spear Steve clumsily gets out of the small dugout canoe into the warm water, Moses follows with barely a splash.

They swim in the vicinity of the canoe looking for small fish on the bottom. Moses spears one, two, three, as Steve struggles to stay down for any length of time. Finally manages to spear one but must catch a breath on the surface before recovering it. After some more unsuccessful forays Steve sees a small reef shark and heads for the surface. Moses signals him into the canoe. There is no great danger but with fifteen small fish of various colours they paddle back to the village.

That evening before night fall Steve sits on Moses’s veranda eating an evening meal with his young family, the roast fish a welcome addition the sweet potato and cabbage. Moses’s wife, Evi was very shy at first but now is comfortable and engages with him easily in pidgin. Their 18-month-old blond haired daughter treats him like a big toy and Steve plays along. After he’s finished eating, he picks her up on his hip and walks through the village to the shore. Great belly laughs come from some of the houses as they pass.

“My Mrs says you, manevake, are a fast worker. You’re only here a few days and got a pickinny quick time.” Silas’s shouts to him.

“Your Mary knows too much!” Steve retorts in pidgin, to more whoops and laughs, enjoying the joke is on him.

The tropical darkness falls quickly in a kaleidoscope of pinks, mauves and deepening blue. When Steve returns the child is asleep on his shoulder. Silas and some others come and join them to sit or squat on the veranda. They have heard that Steve can tell a story or two.

Evi produces some betelnut which Steve manages to chew until he feels a mild buzz, then to great amusement, he coughs and spits out the acrid red mixture over the edge of veranda.

He needs a drink of water before starting his version of the Finn McCool and the Scottish giant, stomping and roaring in frustration as their causeway refuses to rise from the sea. When he finishes, there’s more betelnut, Steve refuses this time, and Silas starts a stream of funny bawdy stories.

Steve yawns, moves to leave, and with him the small crowd dwindles.

Concluding part in next blog.