An essay – revised August 2025

A couple of years ago, I had a short story published in an Ulster-Scots book, Yarns. It was about a fictional character, loosely based on a distant relative, who underwent a religious conversion during the Ulster Revival, transforming from a wastrel to a devout Christian man. It was written in a mid-Antrim dialect of English, but revised into Ulster-Scots and published under my name, without any acknowledgement to the translator. The revision seemed minor, but I struggled to read and understand much of the new version. This unease has returned to me occasionally, alongside a reticence to assert Ulster-Scots as a distinct language and culture. Here, I have tried to throw some light on these misgivings: what are the roots of Ulster-Scots, and indeed what would make it a language?

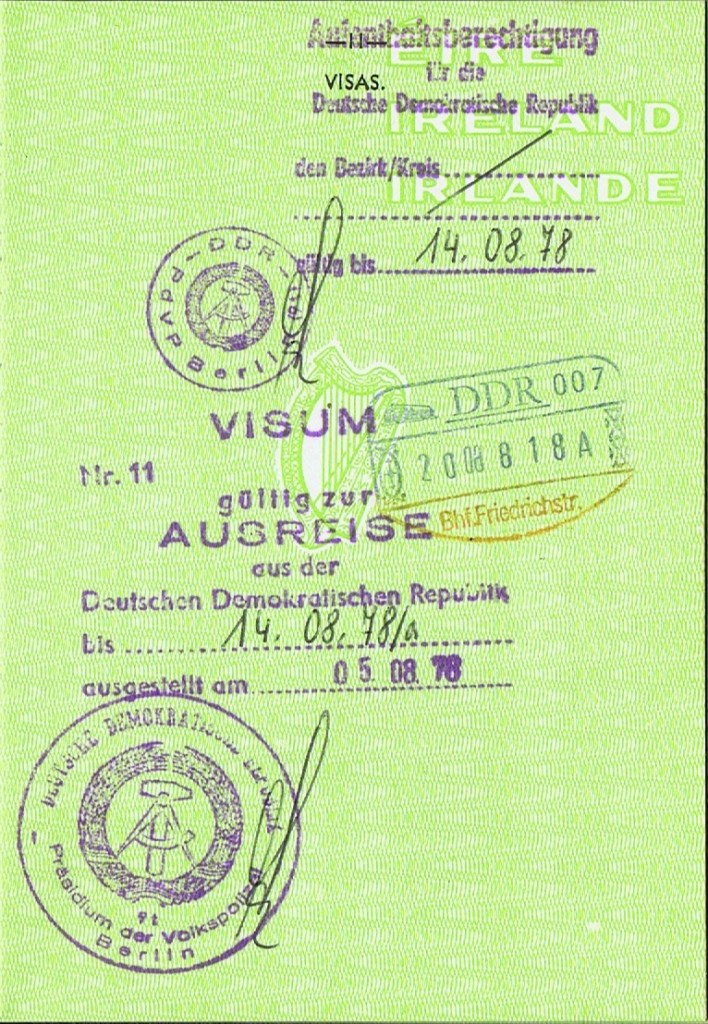

The term Ulster-Scots, and its precursors, were used by early colonists in North America. These were Presbyterians from the north-east of Ireland who were initially referred to as Irish. Around the 1770s, they adopted the name Irish-Scots to differentiate themselves from Catholics and express their Scottish affinities; then it was quickly turned around into Scots-Irish.

They were libertarian Calvinists. Their allegiance and loyalty were primarily to the God-anointed King, and their libertarianism made them suspicious of parliaments and governments, prone to take restorative action when they considered it necessary. History, they later felt, justified this wariness of what often turned out to be unjust authority; notably, in the decades after their involvement in the Siege of Derry.

The Westminster Confession of Faith, drawn up in 1646, appeared to copper-fasten a Calvinistic, strongly anti-popery religion across these islands. However, this Calvinism all but disappeared among modifications to establish the Church of England, and later, as the Protestant Ascendancy became dominant in Ireland. The Presbyterians’ refusal to accept this new religious authority reduced them to second-class citizens, barely above the native Irish.

As a result, tens of thousands of Presbyterians left Ulster in search of a new world in North America. They led wars against indigenous American tribes, colonising their lands, making a name as frontiersmen and European pioneers. During the American Revolution, they took the rebel side with gusto. Captain Johann Henricks, a British Army officer, said of them, ‘Call it not an American rebellion, it is nothing more than a Scotch Irish Presbyterian Rebellion.’ And they were also influential in the formation of the United States Constitution. The Second Amendment – the right to bear arms – is an outworking of their Calvinistic libertarianism and the suspicion of government. In the United States there was no use of the term Ulster-Scots until much later when it migrated from Ireland.

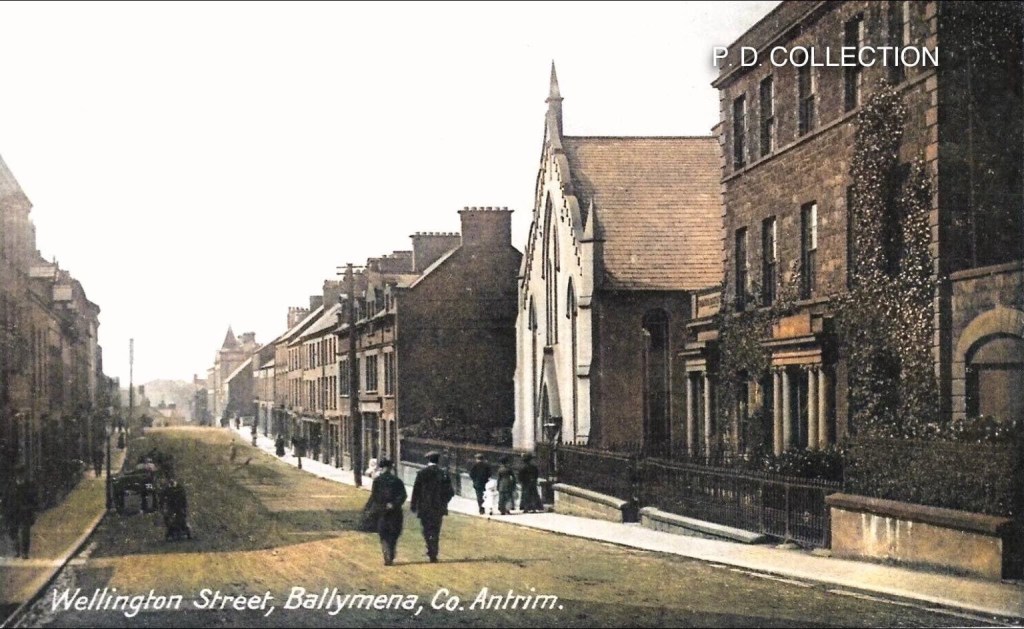

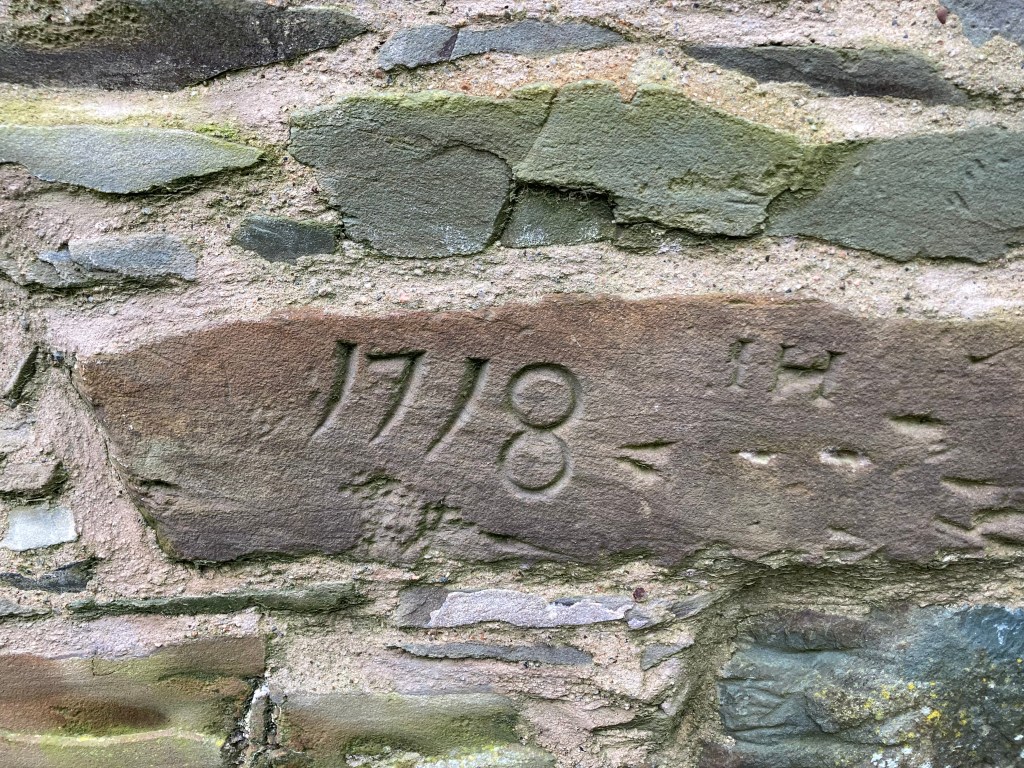

The self-descriptive term has morphed over the years from Irish into Ulster-Scots. The Ulster-Scots Agency says the term has been in use since 1640. The Ulster-Scots Language Society was established in 1992. I grew up speaking a mid-Antrim dialect of modern English, a rough tongue my mother might have called it, and used many words that appeared in recently published dictionaries: Ulster-Scots grammar and dictionaries by Fenton and Robinson, and Dolan’s Dictionary of Hiberno-English and in Share’s Slanguage. Fadge, I’m glad to see, which is common now in the Ulster fry, is in these dictionaries as griddle-cooked potato bread, although the word’s origin appears unknown. A cross-over food, perhaps?

Few outside Ireland, and those who describe themselves as Ulster-Scots, are familiar with the term. In recent years, particularly since the implementation of the Good Friday Agreement, Ulster-Scots has moved centre stage and been at the core of contentious political issues. Is it or is it not a language? A language that is part of a distinct culture? As in many things here in Ulster, your answer to these questions defines your identity: Protestant or Catholic.

So, what is a language? Does it define a distinct culture? English? Mandarin? Spanish? Mayan? Surprisingly, academics don’t appear to have a clear definition. Max Weinreich is attributed with the statement, ‘A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.’ That sounds rather trite until you think about it. Chamber’s Dictionary defines language as: human speech; a variety of speech or body of words and idioms, especially that of a nation; any manner of expressing thought or feeling. A friend reminded me, I’m using language to try to describe what language is. Tricky indeed.

The border regions of France and Belgium speak mutually understood French and German dialects, as do the border areas of Germany and Denmark. Then, what about Scottish Gaelic and Irish Gaelic? They are very close. Yet central governments decide what is the nation’s official language, and what language school books are printed in, for example.

While Weinreich’s statement about language carries weight, it assumes an authority that corrals and overrides the interests of minority languages. However, the scale of a country’s territory can demand different solutions. India, for example, has twenty-eight official languages and many secondary ones.

Many regional dialects and languages are closely tied to identity, and language rights are common at the forefront of political conflict. Within Europe, in recent years, there has been a growing interest and support for minority languages. However, there seems to be a natural tension between the desire for a centralised and national language, or languages, while the reality of our lived experience is an ever-changing patchwork of dialects and languages, however defined.

For most of human time, sea routes carried trade in goods, and as an unintended consequence, language and culture. The centuries-old sea routes on the Sea of Moyle up to Scandinavia, down the Irish Sea, were dominant when our inland routes were practically non-existent. Traders and raiders carried languages and dialects of the Gael and Vikings, Saxon and Norman, the skill of linguists among them easing communication and reducing suspicion. Words and phrases were exchanged along with goods.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century after Ulster, the last Irish Gaelic stronghold, had been razed by an English scorched-earth policy, it was left almost devoid of people, and the native tongue had all but disappeared. New languages, dialects and cultures were carried by the incoming lowland Scots and English during waves of plantation. To a small degree, these same Scots carried a version of Gaelic westward. Certainly, it was used by Presbyterian preachers wanting to convert the remaining native Irish. Ironically, it turns out that many of these Scottish settlers also carried Irish Gaelic genes, the legacy of Irish raiders who had remained in Scotland centuries earlier.

Wesley Hutchinson, a Professor Emeritus at the University of the Sorbonne Novelle, has published extensively on Ulster-Scots. Like me, he is a native of mid-Antrim and has an affinity with the words he grew up using; words he, too, was often told were wrong. Hutchinson examines the historical evolution of Ulster-Scots into its recent politically driven form, which he describes as a binary cultural “brand”. He makes an interesting distinction between the Ulster-Scots stereotype, which he says is predominantly male, militant and uncompromising, and its literary and theatrical culture, more inclusive and less binary. He offers the latter as an avenue to a more inclusive future. In an interview on NVTV Belfast following the publication of his 2019 book ‘Tracing the Ulster-Scots Imagination’, he concludes, when pushed, that Ulster-Scots is a Scots dialect, of Scot-English, I presume. I would agree, but adding some Hiberno-English, Old English and Irish Gaelic to the influences.

Regional accents and dialects have become more common across our media channels, though, to many, they don’t rank highly on a scale of culture. Which is ironic given the root of the word culture itself: the tilling of the earth and in the plough’s coulter. The working of the earth, which is the very birthplace of dialects and languages.

On reflection, then ‘A language is a dialect with an army and navy’ sounds not too far wide of the mark. Dialects and languages, like clouds, gather, mingle and diffuse, blending and continuously changing shape. And so, with Ulster-Scots. I hope all this bletherin doesn’t make your head birl. And it sounds like herding cats to me. But then I like cats.

Notes on references:

The Scots-Irish: The Thirteenth Tribe, Ulster Ancestry, Robert James Williams, facebook post 2019. Available at the link.

Marianne Elliot, Watchmen in Sion: The protestant idea of liberty, A Field Day Pamphlet, 1985.

Tracing the Ulster-Scots Imagination (Belfast, Ulster University), Wesley Hutchinson, 2018. Wesley Hutchinson works almost exclusively on issues connected with Ulster-Scots history, literature and identity.

Presbyterians and the Irish Language, Roger Blaney, Ulster Historical Foundation, 1996

A Dictionary of Hiberno-English, Terence Patrick Dolan, Gill and Macmillan, 1998.

Slanguage – a dictionary of Irish Slang, Bernard Share, Gill and Macmillan1997.

The Hamely Tongue, James Fenton, The Ullans Press, 2014. First published 1995.

Ulster-Scots, a grammar of the traditional written and spoken language, Philip Robinson, The Ullans Press, 1997.

Chamber’s Dictionary, 2024.