This blog arose from previous family history posts, a few loose ends that had puzzled me. The first two of these are tidied up with the answers that were in plain sight, I hadn’t realised their significance. The last is perhaps frivolous.

Firstly, I only recently realised that both my parents grew up in families dealing with the consequences of their collapsed family enterprises.

Hugh McWilliams, paternal grandfather, had a thriving coach-building business which collapsed with the rise of the motor car.

Richard and Annie Davis’s County Leitrim family was thrown into a crisis of debt when Richard’s business partner absconded to North America with the assets of their cattle business.

These early decades of the 1900s saw major political tension and flux, which culminated in Irish independence and partition. While both families were Unionist, with connections to the Orange Order, they ended up on either side of the new border.

Each family adapted to changed circumstances. Hugh and Lizzie abandoned their home and Hugh’s workshop for a smaller two-up two-down house. Hugh went out to work as a jobbing carpenter, and it was said that he became somewhat of a recluse. Richard and Annie’s family was deeply in debt for many years, finally reclaiming the last of the mortgaged farm in the 1940s. These decades proved exacting for the growing family of nine, compounded by the loss of toddler Maureen in 1923 and Herbert at nineteen in 1939. Despite their prosperous-looking two-story slated house overlooking a main road, neighbours could easily tell the family was in dire straits, and spending had been cut to the bone.

The second insight was that Robert McWilliams, my great-grandfather’s second marriage in 1867, noted as a civil marriage that could have been in a registry office, was to Eliza Bamber, fifteen years his junior. Eliza was pregnant at the time and Ann, their first child, was born four months later. Ann died of TB at the age of nineteen.

Is this a likely explanation of my Aunt Martha’s single acknowledgement of him with a shake of her head and a look of disgust? And the reason for our strongly Presbyterian family’s disinterest in their ancestors and relations? Were they ashamed of their past? Nothing is known of Robert’s first marriage or how it ended.

James Boyle, writing in 1834 in the Ordinance Survey Memoirs says: Ballymena people are a rather moral race – though the number of public houses there being 107, would lead one to suspect otherwise – they are indeed fond of whiskey and too many indulge in it. On Saturday evenings the number of drunkards on the streets is disgraceful, but they are mostly from the country.

Robert was from the country. He moved into Ballymena following his second marriage and joined Second Ballymena Presbyterian Church, where I suspect he became an earnest member, and raised his family in strict faith and observance.

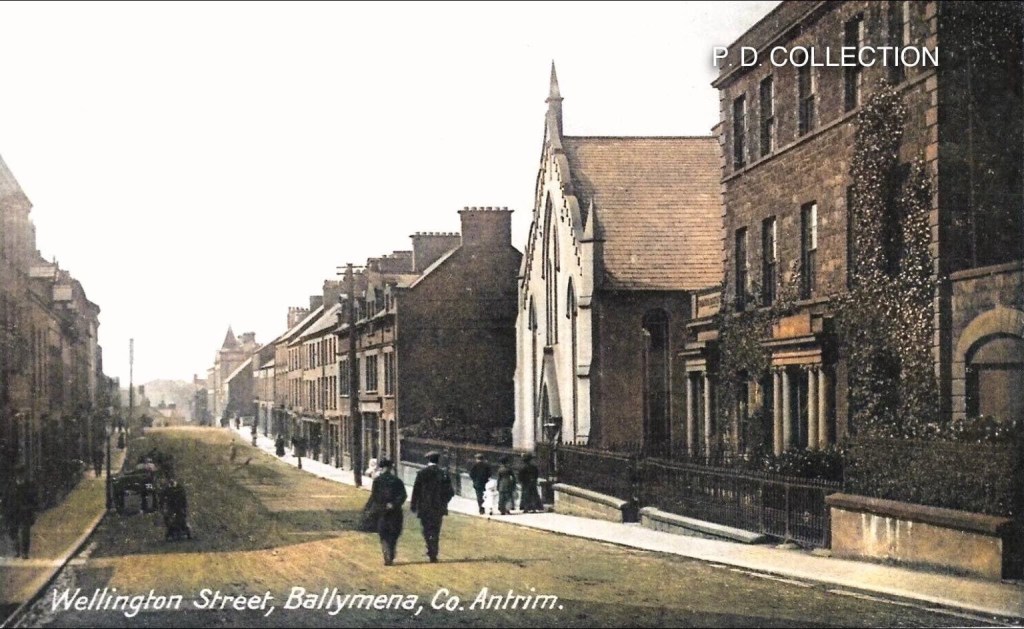

Robert and Eliza’s church, second building on the right, when they moved to Ballymena after their marriage in 1867, living a short walk away in Alexander Street.

The major expansion of all churches in Ireland and beyond during the mid 1800s was driven by zeal to rescue the general populace from sin and immorality, mainly drunkenness and promiscuity. Shame and guilt proved significant drivers of the increase in church numbers and the subsequent period of new church building. Robert and Eliza were among these new converts.

Lastly, a memory from my grandfather’s knee, where Granny often fed me buttered bread with sugar. One evening, Granda raised a finger to one nostril and blew some offending material out the other and into the wide hearth. Funny how some things stay with you.

So, what it this called? – blowing mucus, snot, down one nostril. It’s common among farmers and outdoor workers, among cyclists and runners. A male thing, perhaps? Searching in English, only slang turns up, a farmer’s blow, which seems appropriate, and a snot rocket. There’s no medical term I can find.

So far, nothing in Gaelic, but the closest might be Smuga a chaitheamh amach, (SMUH-guh uh KAH-huv uh-MOHKH ) to expel snot – a phrase my mother might well have remembered with her achievement of a Silver Fáinne medal. I’ve asked around Buncrana with one positive reply – in West Africa’s Yoruba, the word is, fumu, short and explosive, as it is.