It all changed the year Richard got married. A year of turmoil it was. Sein Fein won the election, many of our men didn’t vote, a few difficult days with neighbours. I had to fight for my place here too, after more than ten years of runnin the house. And Alec was gone, married and livin in Meath. No one to back me up.

Richard and Annie were married in Dromahair Church a month before the armistice was signed and the Great War ended. It was only startin here.

She arrived her gosling wings barely gone, thinking it’s hers to run. Reading her books and poems, ways like the gentry, lucky to get Richard at all, she was. Oh, we’ve had it out manys a time, at it hammer and tongs sometimes. I had my ways, knowin the place like I do, she had hers. No Alec to come between us. Richard coming down on her side. Eventually she got her way, when the first childer were born; I suppose it was only right too. Arragh, I can be far too head strong for my own good.

Now they ignore me. Alec smiles at me, asks am I alright? What does he think?

It was some shock ten year ago when Richard lost it all, everything, I mean all we had. It seemed to be goin so well. Settin himself up on his own terms, makin great profit from the cattle shippin. Behind his back some said he was too soft, didn’t have himself covered well enough. But that blaggard, the crook, the, may God forgive me, the names I’ve called him, he ruined us.

Days of turmoil and tears, slowly seepin in what had happened. The loss of the money, yes, but the debts, God help us, we were finished, the Bank wantin everything. The Rector called, prayed like it was a death, didn’t make it any better.

Three of us and the childer, when it happened. We had a man as well, Robert, Robert Maxwell, but we had to let him go. The days passed and we learned to live with less, the childer knew nothing. A felt sorry for Annie now, a baby arriving almost every year. And fair play, she fell to it, what else could she do. Worked harder, made all our clothes, nothin too low for her now. Look at us, in our big slated house, puttin a brave face on it; sold what we could, worked ourselves harder, bought little. We ate so much salted herring in them first years, I’m sick of the sight of it.

And the bank keeps chasin us for more, putting the place up for sale every year, we could be on the road, God help us. But Richard dug in, his faith behind him. He would pay it all back, he said, the farmers, shippers, John in Meath, all of them, get going again, he said. God help us.

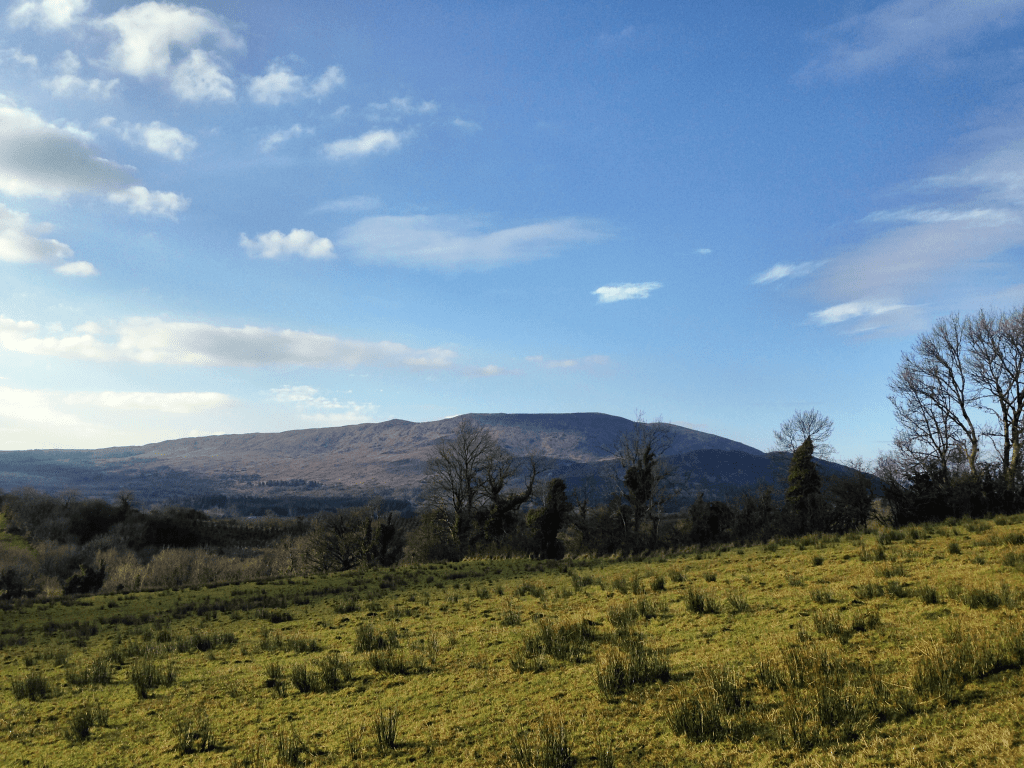

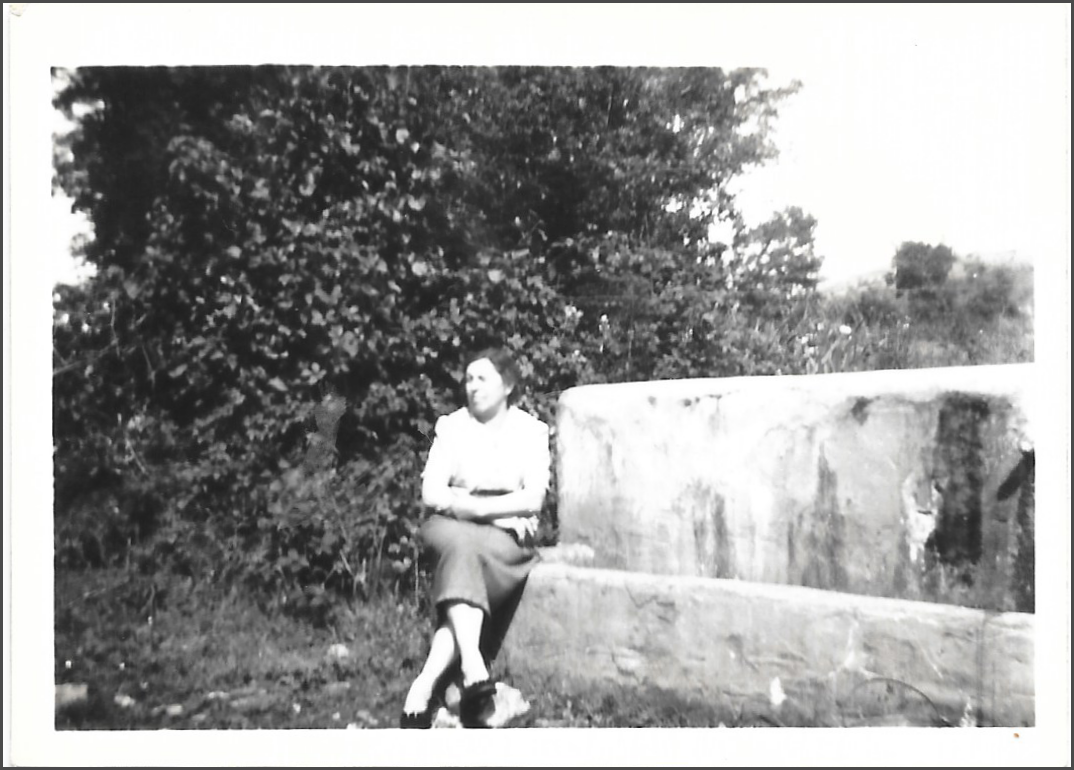

I always kept the garden, you know, the big one up beyond the White Field. Loved my time up there, grew fine rows of cabbages, carrots and beans in the peaty loam, damp in the driest of years, I could be lost there. I often sung to myself. In bad times pleadin, and prayin to God. I still have a seat up there, although I don’t keep the garden. In the warm summer sun, I’ll go up there sit for a while, get away it from all here and thank God for the life I’ve had.

Ends.

Mary Jane’s brother Alec will feature in the next blog.

Notes

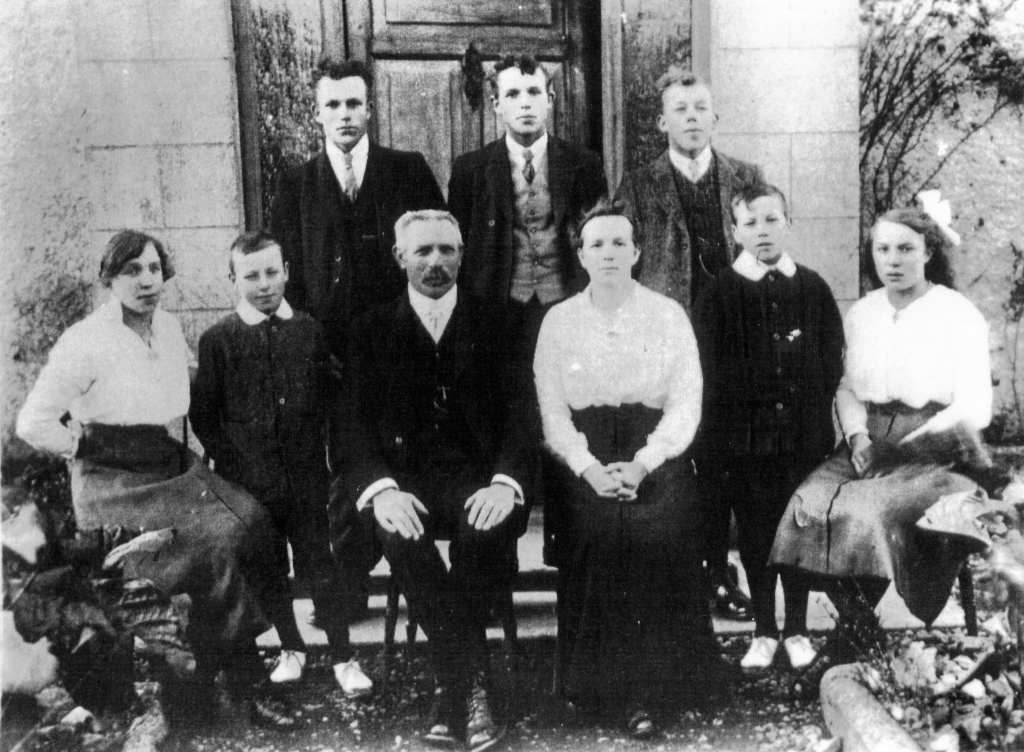

1. I never knew my Grandaunt Mary Jane Davis. This imagined monologue is based on the circumstances and events surrounding her life and a few mentions my mother made of her. It does not reflect the complexity, vitality and colour of her life and I make apologies to her memory for any gross errors in her portrayal.

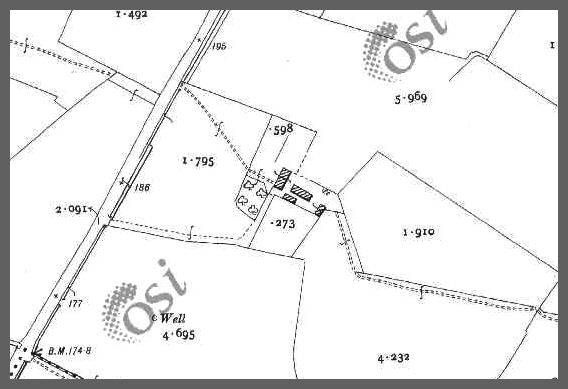

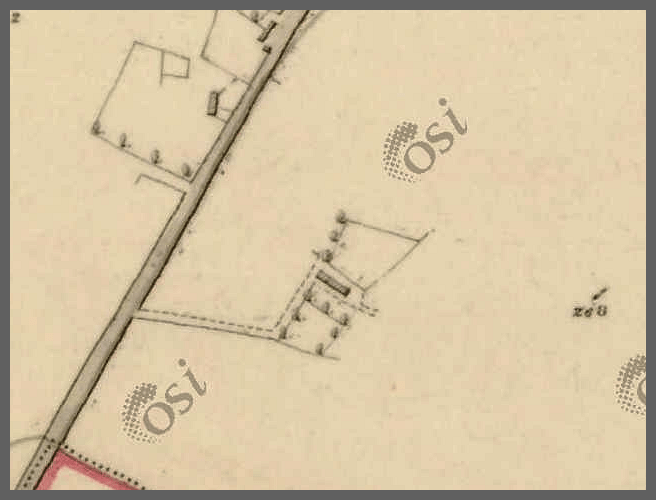

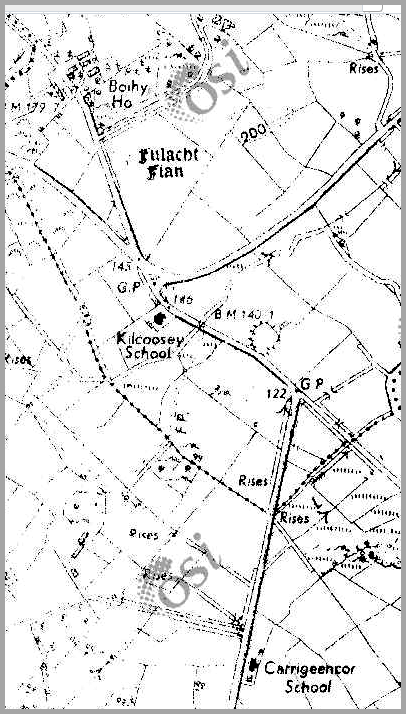

2. The first note on the Valuation Office records in 1862 shows John Davis with 47 acres at Boggaun. Patrick McKay is noted as living here as a tenant in the haggard but not by 1880 valuation, it is presumed he had died. The valuation of 1880 shows a significant increase indicating the new house was built by then. Griffiths Valuation circa 1850 shows John Davis at the same property.

The Valuation Office has a manuscript archive containing rateable valuation information of all property in the state from mid 1850s until the early 1990s; and commercial property only from that time. This archive shows the changes after the revision of properties and is recognised as a census substitute for the period from the 1850s to 1901 (the earliest complete census record for Ireland). The archive may be used to trace the occupiers of a particular property over a period of years. These records are not available online. https://www.valoff.ie/en/archive-research/genealogy/

3. Mary Jane’s father was James Davis born at Glenboy (1833-1909). Her mother was Elizabeth Jane nee Mealy or O’Malley (? – 1910) from the nearby townland of Tawnymanus.

4. Mary Jane’s siblings all born at Boggaun were: John (1861-1931), Thomas (1865-1920) James (1867-1894), Robert (1868-1915), Alexander-Alec (1869-1941), William (1872-1950), Richard (1882-1961).

5. My Grandparents Richard and Annie were married on the 23 Oct 1918 in Drumlease Parish Church, Dromahair.

6. Alec Davis married Margaret Taylor (nee Cartwright, a sister of his brother John’s wife Maria) in 1918 in St Kienan’s Church of Ireland, Duleek, Co Meath. Margaret died 30th December 1928 and Alec returned to Boggaun sometime after that.

7. The blog on the boyfriends of Mary Jane is completely fictious.

8. Neighbours at Boggaun recalled the fiery rows between Annie and Mary Jane and these accounts were recounted by Patrick Fitzpartick to his son Padraig. Thanks to Padraig for this story.

9. I recall there was a large vegetable garden in the location described which had not be worked for several years and finding remnants there including a broken chair. The photograph of the chair above is staged.

10. These blogs on the life of Mary Jane relate to other previous blogs particularly Richard Davis, Swindled.

11. At a later time it is planned to provide a link to related documents where they appear unique, for example, the RIC record of the boycotting of John Davis at Garradice, and various army and RIC records.