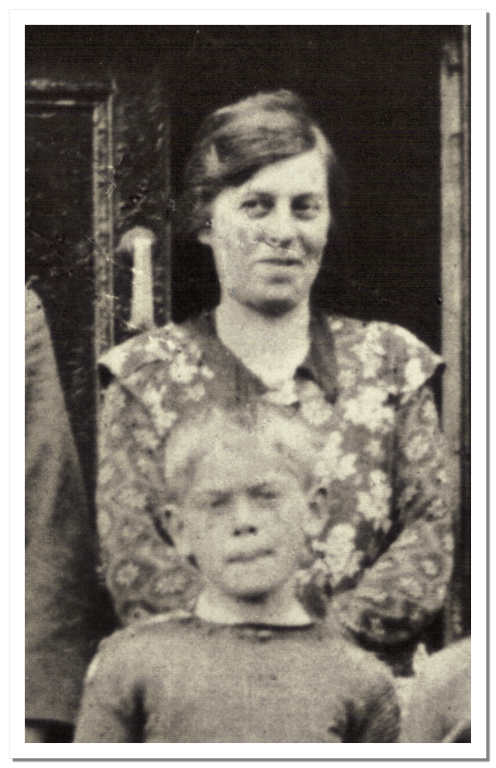

During 1947 and 1948 three Davis siblings left the Boggaun farm, Ena, Phyllis and Alf. Alf was nineteen when he departed and was to make the longest journey to what became his new home. I knew my aunts and uncles to varying degrees. Those who settled in Ireland I knew best and the others less so, only meeting them occasionally over the years. Alf left Ireland before I was born and my first memories of him were on his visits home.

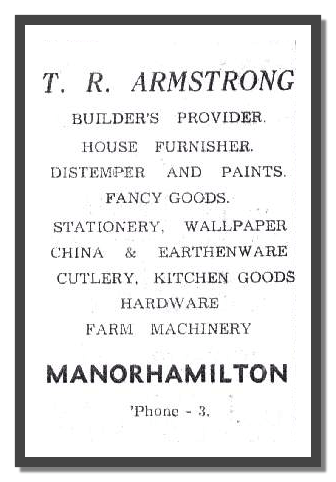

Born in 1929 Alf grew up on the farm and worked hard in those lean years when the family finances were severely stretched. He left Masterson National School at about thirteen to spend a few years on the farm before going out to work in T.R. Armstrong’s hardware shop on Main Street in Manorhamilton. Four years later he was making plans for the long emigrant’s journey to Canada. Unfortunately, he just missed the excitement of the town’s first cinema. It was opened by the same T.R. Armstrong bringing novel picture house entertainment which my mother and her contemporaries regularly enjoyed.

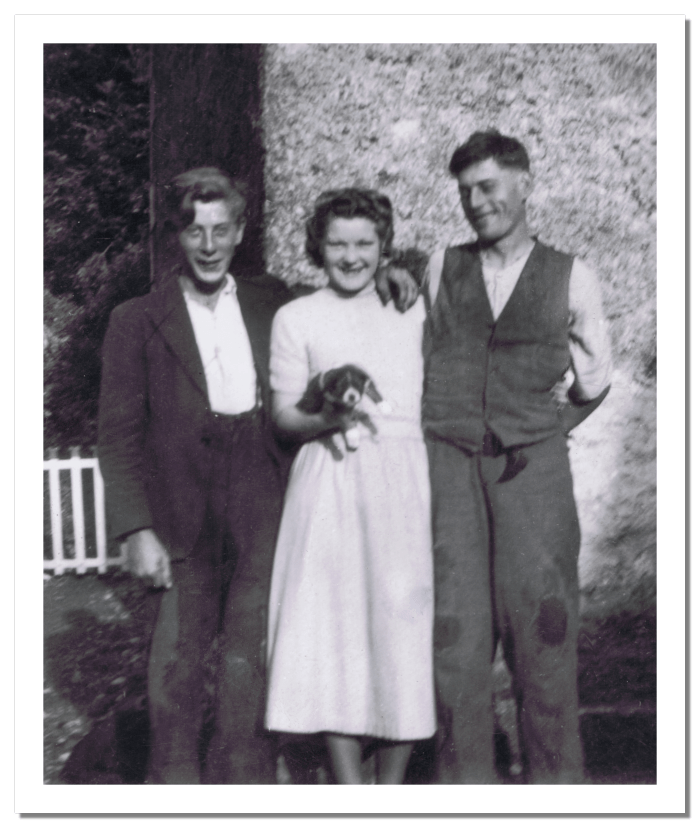

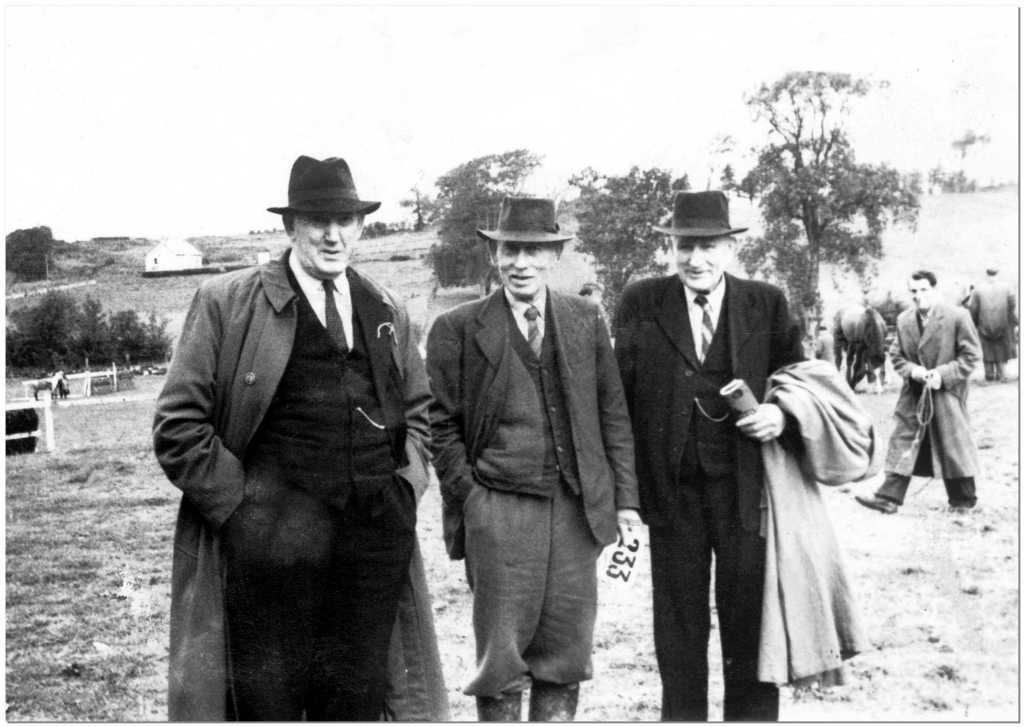

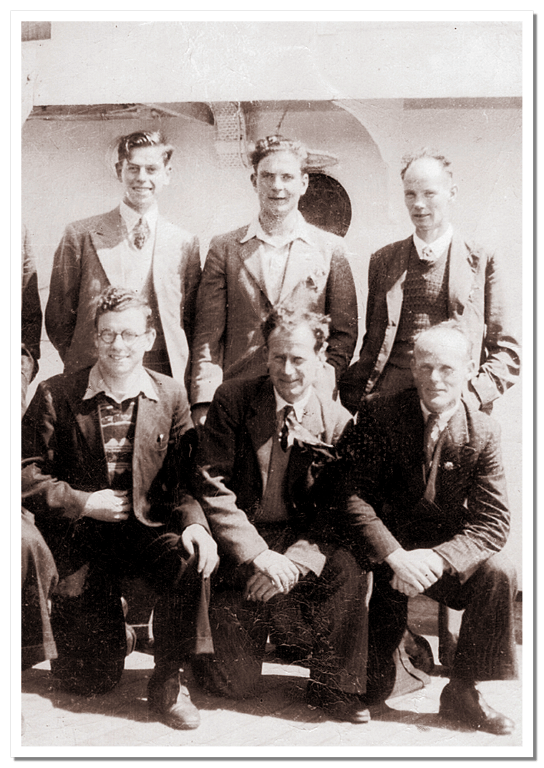

In 1948 Alf, full of trepidation and excitement, was photographed with several Manorhamilton friends onboard a ship leaving Liverpool for Canada. His parents aware of the harsh reality of Ireland at that time encouraged him to go despite reluctant parental bonds. When he landed on America’s shore Alf made his way to Toronto.

Toronto had been the destination of Alf’s Great-uncle Thomas, the first Davis born at Boggaun to emigrate there 1861. He claimed a pioneer’s plot at Amaranth, north of Toronto, clearing forest for farming land; Thomas’ brother John, a Methodist preacher left for the same region two years later, although he finally settled in Iowa. A generation later Alf’s Uncle Thomas emigrated to Toronto in 1886 where the family prospered in the newspaper and real estate business. They all remained in contact with their Boggaun roots. Other families from the Manorhamilton area had also settled there making it an attractive destination for the new arrival.

Alf first worked in a menswear shop but within a few years, through hard work and ambition, he had set up Alf’s Menswear store on The Queensway.

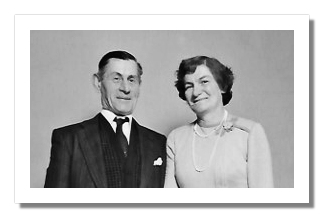

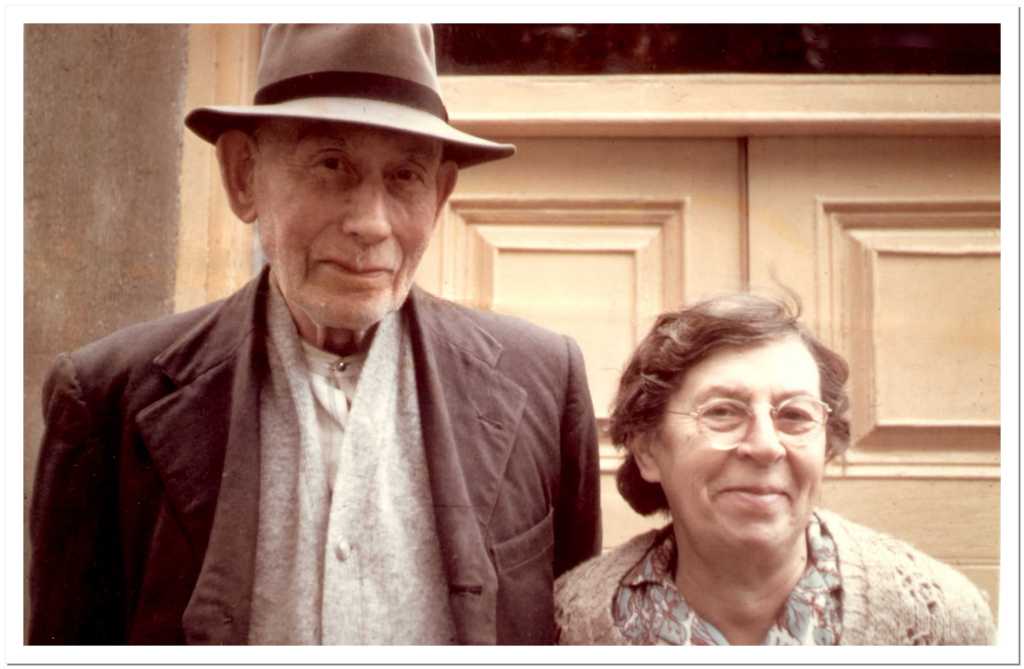

Libby Smyth, originally from Derry, married Alf in 1952. As their family grew and the business thrived, they bought a farm near Shelburne, north of Toronto, with friends Elward and Jean Burnside – the Burnside and Davis families in Canada are related. Alf and his family spent working weekends at the farm, an echo of his upbringing, although not all looked forward to the end of the week.

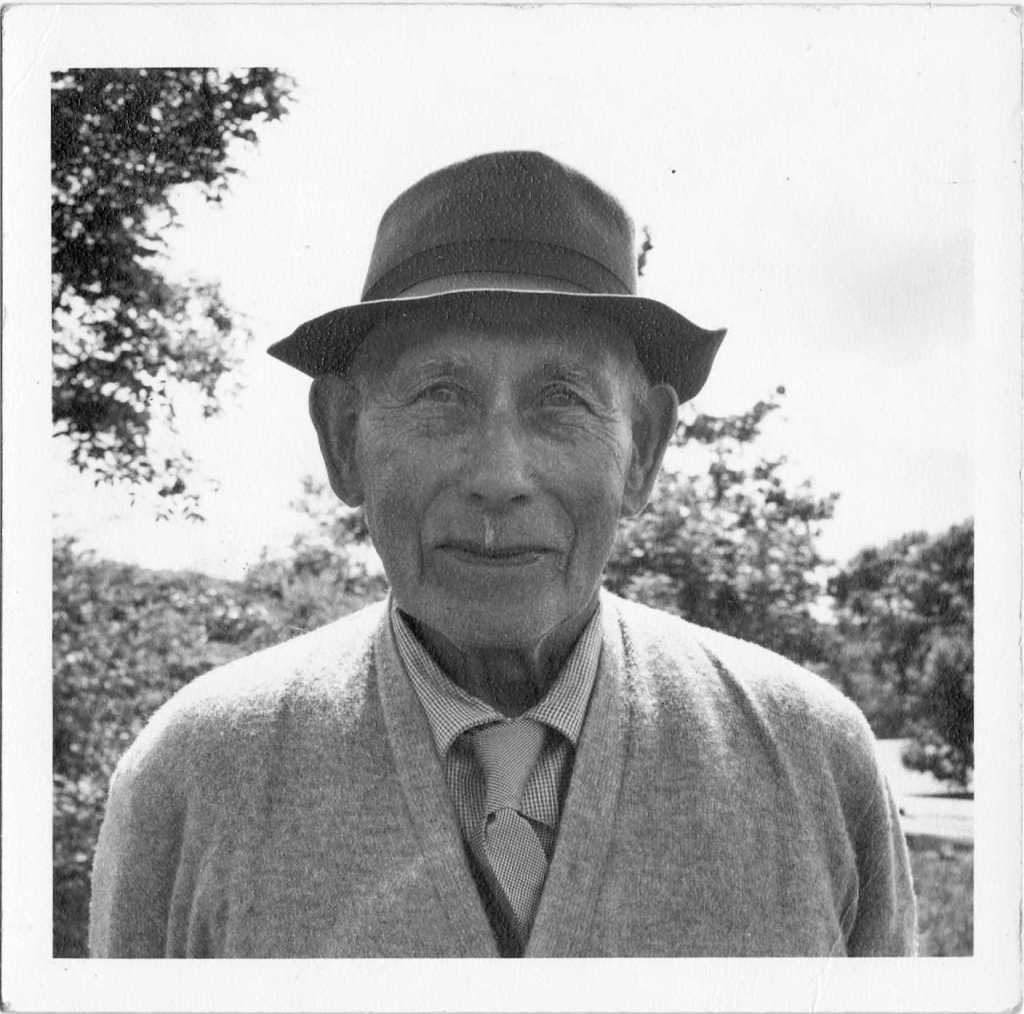

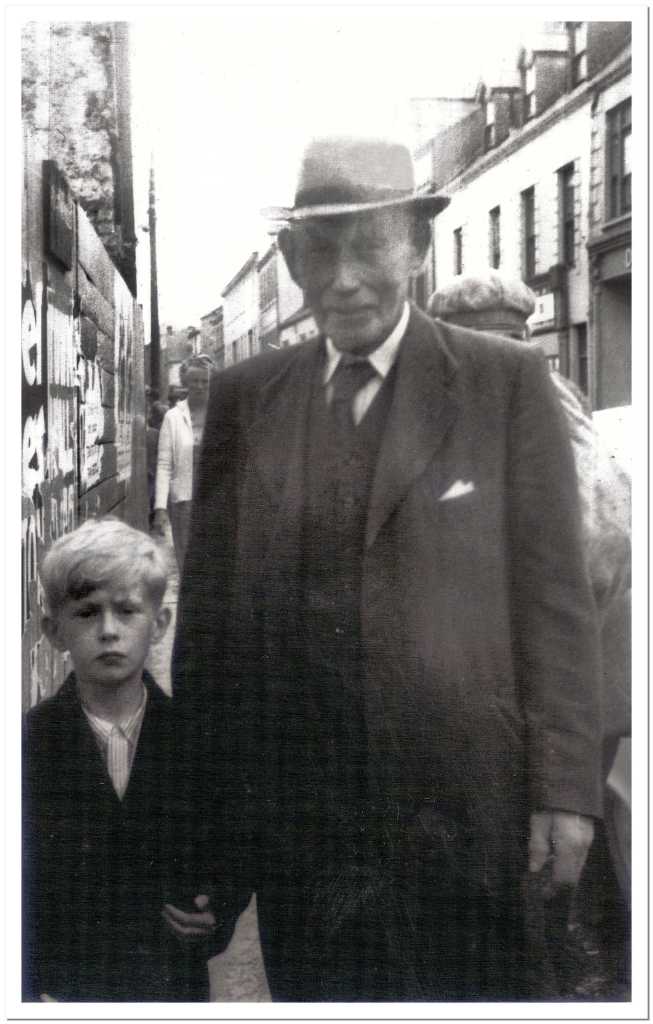

While Alf returned home many times, at first on his own and then with his family, he probably felt at more and more at a remove from his early years at Boggaun. He carried a quiet generous way about him. When Alf first visited us in our Ballymena home, the tall stranger with a deep voice and strange accent, brought a suitcase of clothes for us; two little bomber jackets for my brother and I kept us stylish for months.

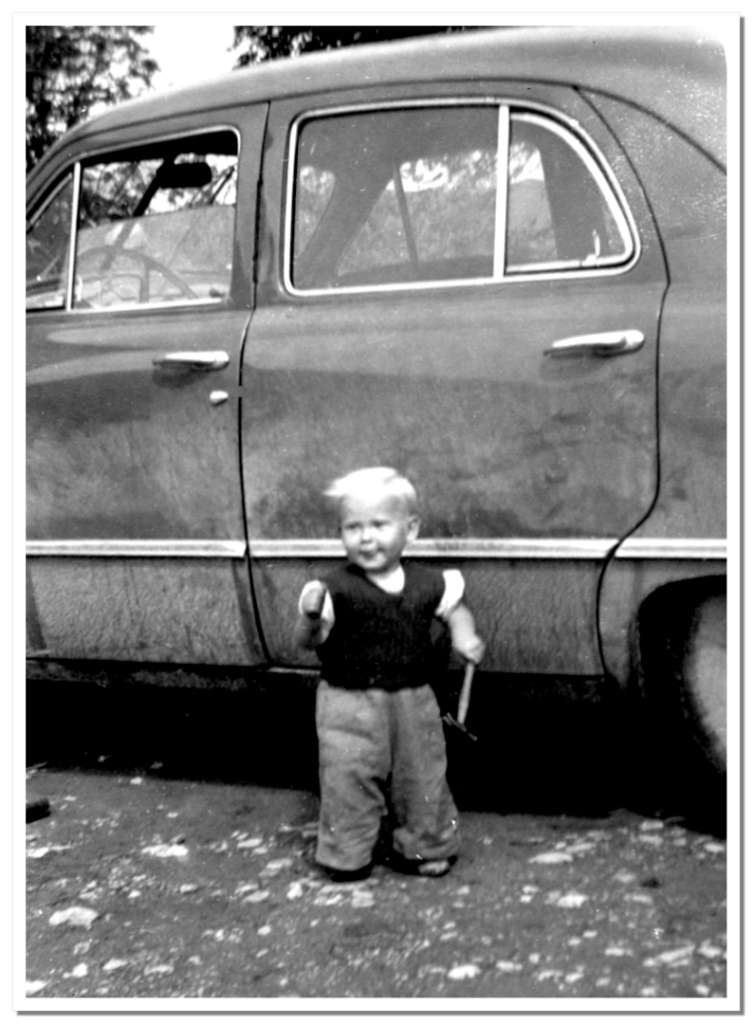

In the summer of 1963, I arrived at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport in sweltering heat wearing my heavy black school blazer and grey trousers. At the age of twelve I had travelled across the Atlantic on a Boeing 707, a substitute for my mother and father, unable to take time off for a summer visit. I was collected at the airport by Uncle Alf and my cousins. In the spacious back seat of the big car, with the warm air blowing through the windows, I was stripped of the heavy layer and then a stop at Alf’s Menswear store turned me into more suitable shorts and T shirt, followed by my first taste of ice-cold coke.

Ten years later as working students, three friends and myself, spent a summer picking tobacco on a southern Ontario farm. Flying into New York, we had arranged to drive to Toronto on a return-delivery before starting work – this was a cheap way to get around North America at the time. We were welcomed by Alf and his family and spent a few days around the city.

Alf generously offered to take us on the two hour drive to the tobacco farm. Leaving the city on the 12-lane Gardiner Expressway we sped west for miles along the populated north shore of Lake Ontario. With the city of Hamilton and Lake Ontario behind us we drove south through rich summer farmland. An hour later we headed out of Tillsonburg on dusty flatland dirt roads towards the shore of Lake Erie, finally arriving at the red clapperboard homestead of Marty Weiss, its high wooden drying kilns and large barns set in a wooded landscape.

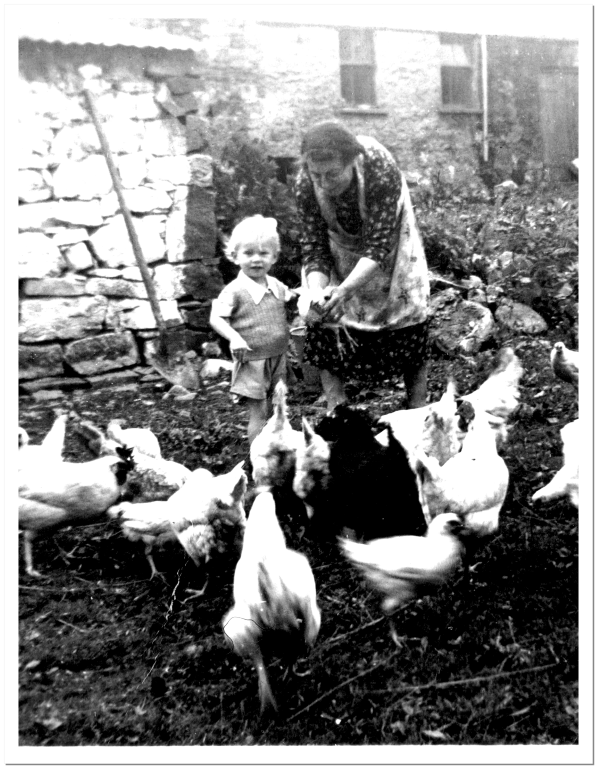

Many Canadians visited their ancestral home at Boggaun over these years, but returning children got special treatment. When Alf and his family were due Granny led great efforts to make ready the house and farm in welcome; road and garden gates were painted, as were window frames and doors, yards were tidied and cleaned, the garden weeded.

But sometimes events would thwart her enthusiasm. On one such occasion when the street around the back door had been cleaned and scrubbed, a large creamery can of fresh milk was accidentally spilt by the farm help who was hung over from the previous night’s revelries. Seeing her clean yard white with milk, Granny lashed him with her tongue and the unfortunate man fled the street threatening to do away with himself. He was found lying up on a dry ditch in the Well Meadow by my mother, Ena, who took the good part of an hour to talk him back to the yard. And tensions went higher when a beautiful salmon tickled out of the Bonet River, plated on the deep sill of the slightly-opened parlour window, was found with the upper side missing after a cat squeezed in to devour it.

Alf Davis and his brother Wallace were the only ones in their Boggaun family to carry the name forward, and after three generations of emigration to Canada most descendants carrying this Davis name are now Canadians.

END