Over the course of researching these blogs I have discovered that four of my great uncles joined the British Army in the late 1800s and early 1900s. There was never any mention of them in the family, nor of their actions during tenant evictions, Empire building and World War One. In the first of four blogs I will endeavour to sketch out the social and political circumstances of their times. All were born near Manorhamilton in north County Leitrim.

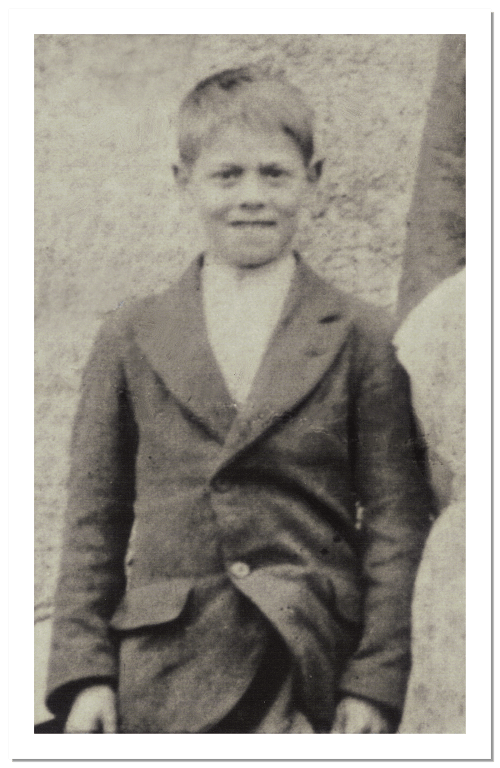

My grandfather Richard Davis is recorded saying that his older brother James joined the army in 1885. Another brother, Robert signed up with the Royal Artillery the following year and their younger brother William enlisted in the South African Constabulary in 1902. My grandmother’s brother Bertie Gillmor, who has appeared elsewhere in these blogs, signed up with the British Army in 1915, taking part in the Battle of the Somme the following year.

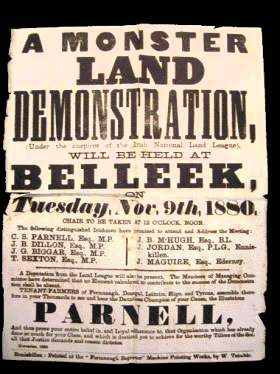

This was a period of great upheaval and change would have clearly influenced the course of the Davis family at Boggaun. With the Famine and the ensuing evictions – which all but saw the disappearance of the landless class, the labourers on small tenant farms – came a greater demand for land reform. Many vacant farms were taken up by existing landlords to graze stock, further increasing land inequality. The Land League was established, following the outbreak of The Land War in County Mayo in April 1879, to coordinate and progress agrarian agitation and reform. Two years later it was suppressed by the government but re-formed under a different name with Charles Stewart Parnell at its head. Effectively the land war continued with the additional focus on the attainment of Irish Home Rule.

Conflict with landlords, many absentees, increased and with it, rural violence and crime. For the most part allegiances fell as you would expect; Protestants supporting the status quo and the link with England – although initially Protestant small-farmers had supported agitation for a great access to land – and Catholics supporting land and political reform championed by Parnell’s party. As the century turned political resistance hardened and fermented into the Easter Rising, the War of Independence and eventually Irish Independence in 1921.

During this time tensions were high in rural Ireland peaking in 1881 and 1886 when agricultural prices collapsed, and evictions increased. Local crimes, which were not supported by the Land League, were for the most part confined to the writing of threatening letters but best known were the boycotts of Landlords and ‘land grabbers’. These had started in a campaign ostracising the County Mayo land agent Captain Boycott in 1880. Throughout the period tenant evictions enforced by the Landlords were supported the police and the army, further convincing the bulk of the population that the government was intent on repression not reform. The Land League were particularly active in the west and north west and campaigned against police (Royal Irish Constabulary) and army recruitment.

The Land League branch in the parish of Killanummery, next to Boggaun, was the subject of a letter to the Sligo Champion in January 1881 reporting that the new branch had brought enough pressure to bear on local landlords that the majority reduced rents to tenants by fifty percent, and in some cases all arrears were written off. It is likely that rents at the Davis farm were reduced at the same time. When James joined up in 1885, there were eight siblings living on the small farm with their parents; my grandfather Richard was the youngest at three years of age, William was thirteen, Alex sixteen, Robert seventeen, James eighteen, Thomas twenty, Mary Jane twenty-one and John twenty four. With agricultural prices beginning a catastrophic fall, the older boys had few prospects for their futures.

Ten years later in 1895 John, the eldest brother, was married and living in South Leitrim. With his Manorhamilton friend, John McCordick they were boycotted as ‘land grabbers’ having moved onto evicted farms near Garadice lake. Whether related on not, John appeared to fall out with his parents around this time. RIC records of the time show details of the boycott against John and his family. The case was mentioned in the press and in the House of Parliament in Westminster, to highlight the mess of the Irish land policy and evictions, and exemplifying McCordick, suggesting he was fraudulently trying to avail of an evicted farms relief scheme which was operating at the time.

The next blog will focus on James and Robert Davis.

End

Note

‘The Land League’ here refers to the ‘The Irish National Land League’ established in 1880 and, following its suppression, ‘The Irish National League’ established to take its place in 1882.