John Christopher Davis was the youngest of the family. He emigrated to England in 1952, aged 20 and then on to New Zealand in 1957, but returned to Ireland seven years later. At home and with his family he was Jack, as he was in New Zealand and it is Jack that I use here. On returning to Ireland from New Zealand he used John.

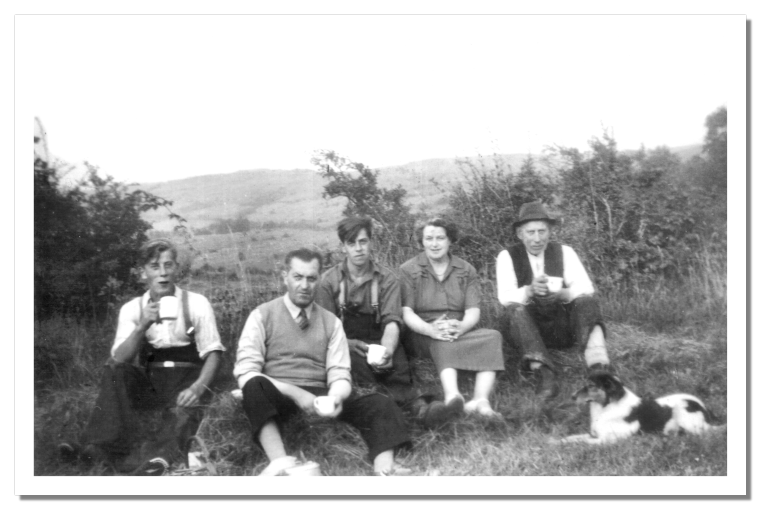

Jack was born the seventh surviving child into a household of eleven, ten years after the worst of the family’s financial crisis. The novelty of a new baby had worn off by then and a good deal of his care fell to his sisters Ena and Phyllis. Jack’s aged aunt Mary Jane and uncle Alex were living at the time and it is easy to imagine the household into which Jack arrives, throbbing with life and activity; the busy mealtimes, hectic mornings as some go off to school the others to farm work, long bedtimes gradually filling the three upstairs rooms, some partitioned off, full of beds and cots.

By the time he went to Masterson National School in Manorhamilton he travelled on the family ass and cart, the only one not to walk to school. A year or two later on an errand to the town, on the same ass and cart he was stopped by the Guards as the poor ass was unshod. His age got him off and he carried home the verbal warning.

He laboured on the farm like the rest of them producing the crops and livestock that would eventually help settle the farm’s debt, but Jack was not destined for a life on Leitrim’s dauby clay. At The Tech he was an eager student and was soon applying what he learned. He expanded the vegetable garden, planted more apple trees and set up a small apiary. With an aptitude for carpentry he made furniture and cabinets for the farmhouse. But at a time with few employment opportunities and when emigration was peaking again, he set his sights on England as his best hope for the future.

Jack left home in 1952 for London with a small nest egg from his parents, like the rest of the family’s emigrants. In London it was relatively easy for him to get work among the many Irish arriving there at that time. His skills were quickly evident and with his attitude to work he was welcomed on many building jobs. Among these were the renovation of London’s historic buildings including Buckingham Palace where he further developed his craft. By comparison to Ireland busy central London offered the young man work, money in his pocket and plenty of ways to spend it. However, he had an eye on distant shores.

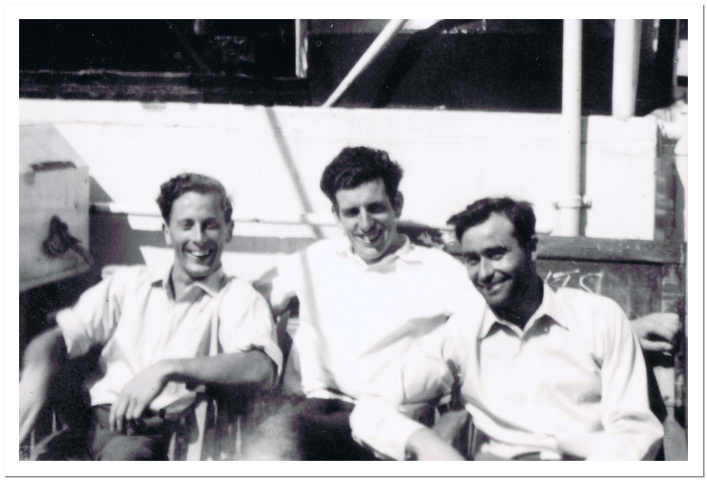

In 1957, along with a group of London friends, he bought a passage on the MV Captain Cook, a New Zealand government-owned emigrant ship bound on a 33-day voyage from Glasgow to Wellington. He was excited, saw adventure ahead of him, his appetite whetted by the hubbub of the 1000 passengers or so, most emigrants like himself. A brief stop in tropical Panama before crossing the equator, and he was on his way to a new life far from County Leitrim.

Palmerstown was his final destination on the north island where the New Zealand embassy had given him contacts for work and accommodation. He worked on a variety of construction projects including extensions to the hospitals in Rorotua and Wiaroa in Hawke’s Bay. He enjoyed the outdoor lifestyle, the warm seas and temperate climate, and with his outgoing nature made many friends.

There were whispers at home that he left in a hurry. Whether pursued by the taxman or string of broken hearts was never made clear, but Jack left Auckland for Southampton in April 1963. This time the ship, the MV Fairsea, navigated in the opposite direction calling into Singapore, Colombo, Aden, Suez, Port Said and Naples, an exotic trip in itself.

I first set eyes on Jack, my youngest uncle when he returned from New Zealand. He was tanned and healthy, travelled and modern, and carried himself with a certain swagger, perhaps feeling he had outgrown Boggaun and Leitrim. He kept himself tidy, his hair groomed to a natural wave.

Jack returned to his old bedroom, the one used by Cecil, and myself and my brother on holidays; its two iron-framed small double beds with sagging springs and mattresses. His heavy-duty suitcase sat on the floor for a year or more, eventually rummaged, it was half full of exotic gifts, Maori trinkets and discarded personal effects.

Jack brought back a small reel tape recorder and a portable radio. It was on this I discovered Radio Luxembourg and its Sunday night Top 20 Hits and with Jack’s help I was soon recording some of my favourites on the tape recorder.

He returned from New Zealand bubbling with antipodean experiences and a head full of ideas. It appeared to him that his brothers were farming the same land, growing the same crops, and burdened by the same damp concerns. But just as a friend’s holidays snaps that can quickly glaze the eyes, Jack’s stories and notions soon fell on deaf ears.

That same summer he organised a trip to the Galway races; he enjoyed a flutter on the horses, and on stocks and shares. We were there at Larkfield on our holidays and, unusually, my father was there too. After a long drive in two cars, the last section between miles of grey stone walls, we spilled out into the sunny grass car park at the racecourse. Horse racing and gambling were considered a great sin by my father’s family; however, this was easily forgotten on this memorable day at the races. The biggest winnings that day was my find of a £20 pound note, tumbling in the breeze near the bookie’s stalls, lonely and looking for a dark pocket.

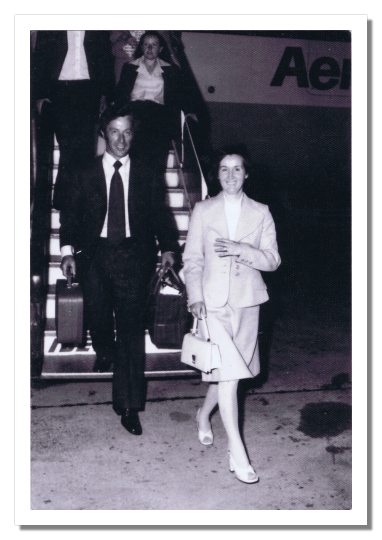

Initially Jack helped around the Boggaun farm, which by then had passed to his mother and would later pass to Cecil, who had managed it since their father’s death. Jack had known for some time there was no future for him here, nor, I think did he want it. Taking up work at Collooney’s Gowna Wooden Industries making windows and doors, he soon felt over used and undervalued. After a year he made a move to Dublin via a short spell in Limerick. In and around Dublin he worked for The Georgian Society and its founder Desmond Guinness whom he got to know well. He found this restoration work most satisfying, exercising his considerable skills and experience. On the outskirts of Celbridge he built his home, “The Bungalow”, with a large vegetable garden, fruit trees and beehives and in 1976 he married Carmel Wylie.

Jack, as Phyllis did, would often offer his advice and wisdom, particularly after he returned from New Zealand. Like his philosophy of a fairer share for the common man, much was unfortunately lost by his brash manner.

“I’m not listening to Jack anymore!” my exasperated mother once said.

On visits back to his Leitrim home Jack’s farming and financial advice also tended to be unwelcomed and unheeded; Cecil, nonplussed, would often fall silent.

His father was swindled, by a Protestant business partner, out of a significant sum of money some ten years before he was born and when the family were still straining from the near bankruptcy. Whether referring to this or his own similar experience, he carried a bitterness against his own kind for displaying such opportunism and deceit. He often warned us with words to the effect that you “trust them at your peril”.

In Celbridge, where he had a wide circle of friends, he was exclusively known as John. Outside of his work he took great pleasure in tending his garden and beehives. When I started to travel around Ireland, mostly hitching a ride, Jack and Carmel were always generous in putting me up for the night and collecting me from whatever godforsaken spot I had landed.

End

Fantastic read, Stanley. A fantastic man, Jack Davis! Lovely to hear the stories and rekindle the memories. Karen Hodgins

LikeLike

Wow! you’re fast Karen! Haven’t got the email out yet! Hope all the family are well. Thanks for the kind comments.

LikeLike

You’re a great storyteller Stanley. Very interesting are all the blogs.

LikeLike

Thanks Joyce. Trust you are all well.

LikeLike