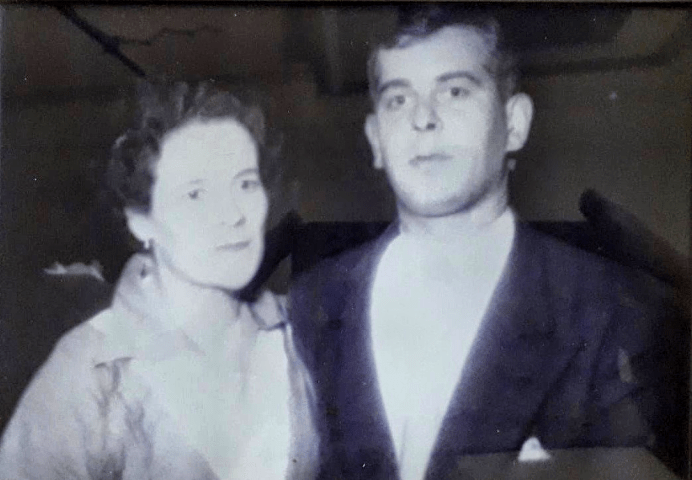

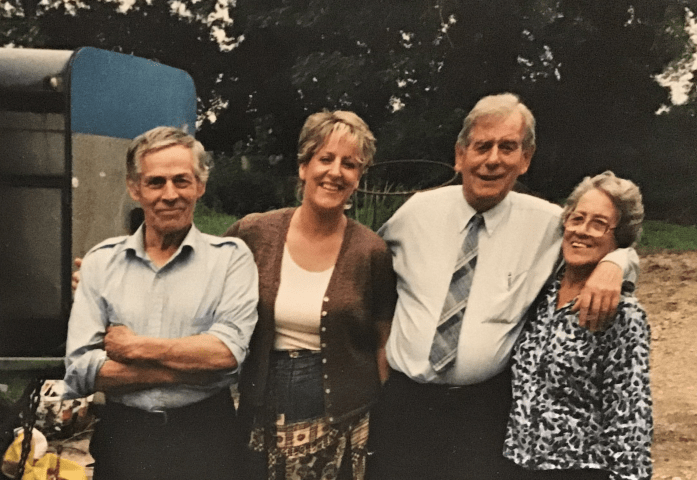

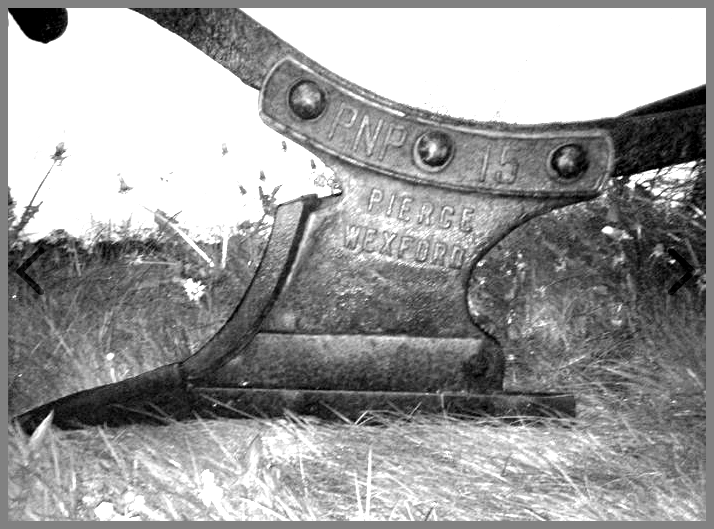

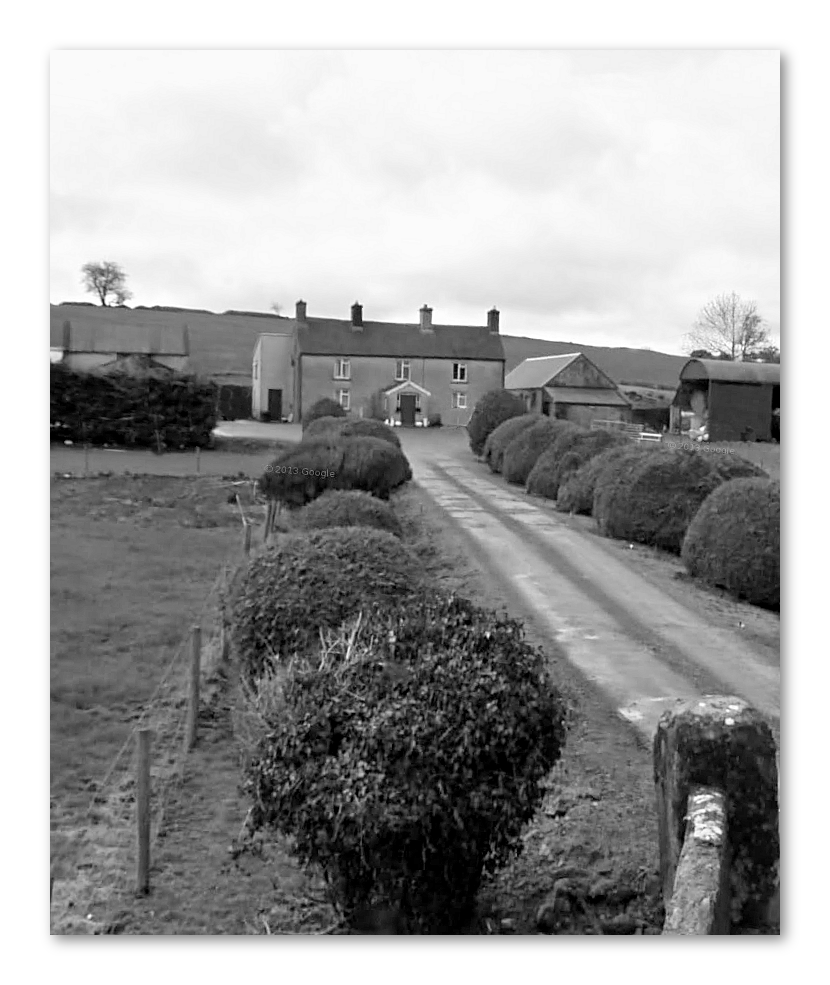

Reco Davis (1921-2011) is my mother’s eldest brother, my uncle. In 1957 he married Dorothy McElroy (1925-1993) and they lived at Woodhill, Bunnanadden, Co Sligo, Dorothy’s home, where they had a mixed farm. We are on Christmas holidays at my Grandparent’s farm at Boggaun in Co Leitrim and make a yearly visit to Woodhill.

On a Christmas visit to Bunnanadden in Co Sligo I first hear of the Black and Tans.

The days are short and the 25-mile journey from Boggaun in Co Leitrim is not one my father likes. We are visiting my Uncle Reco and Aunt Dorothy at Woodhill in Co Sligo. It’s always a journey with some winter hazard. The roads are often icy. There’s fog or sometimes floods. By the time we return to our Grandparent’s farm that night we are fast asleep in the darkness of back seat, some of us lying across my mother’s lap.

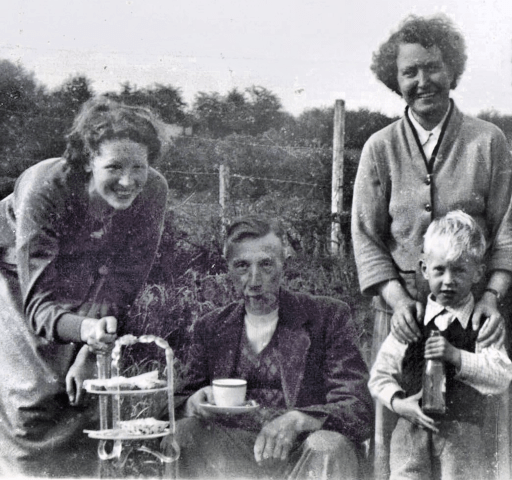

Dorothy puts on a tremendous spread in the dining room, another Christmas dinner complete with a roast goose, ham, cold meats and all the trimmings, Christmas pudding and custard, mince pies and offerings of juice, sherry and wine. She has lots of nervous energy and can’t do enough to make us welcome; when he’s not working Reco is easy going and draws on a regular Sweet Afton. Dorothy is very affectionate towards us; they have no children. Ned, hired by the previous generation as a farm labourer, is now part of the family but is away for the evening.

When we can eat no more, we go down to the lower room where a log is thrown on the fire to raise a flame. The room is warm and a single shaded-bulb casts a low soft light. Occasionally the wind moans in the chimney. I know a 2-fingered version of Chopsticks and I tentatively play it on the old piano.

Dorothy comes into the room and quietly says

“I haven’t heard that tune for so long.”

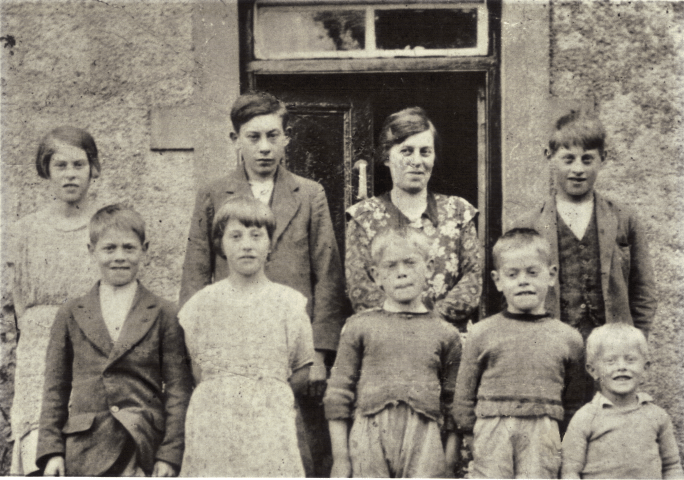

Standing with her back to the piano and with a serious look on her face Dorothy tells her mother’s story of a Black and Tan search of the farmhouse, on a night just like this, a couple of years before she was born. This is Dorothy’s mother’s story.

**

I was the first to hear the motor coming up the lane and ran to look out.

“It’s the police. It’s the police!” I shouted.

My father opened the door to be told that they were searching for guns. They ignored his mild protest that we have no guns and anyway why would they be looking here. The house and sheds would be searched.

The rest of us were huddled in the kitchen, not knowing what was happening. I heard the heavy boots clumping up the stairs, going from room to room, opening and closing doors, knocking on the walls. We were shocked and scared.

It was a few days after Christmas Day and my sister and her family were coming over that night, the lamps and fires were lit in the good rooms.

After they gave up searching, the six of them gathered in lower room, where the piano is, warming themselves around the fire. We were all more relaxed by then. Really, they hadn’t given us too much trouble and had stacked their rifles up against the end of the piano, hanging their caps on the muzzles.

“You play the piano luv?” one of them asked me in a strong London accent, but I just looked shy and when I didn’t answer he said.

“No? Well, some hot tea would be nice then.”

Daddy nodded at me and I went to make them tea. From the kitchen I heard them laughing, then somebody started to play a rough version of Chopsticks.

“Common Joey boy give us something to dance to!”

He just played it faster.

As I came in with the tea they pretended to dance, the floor and room swaying.

“Georgie! stop dancin your too fat, you’ll bring down the floor!” The loud one, Sam, says.

“Sorry luv, we don’t often get a chance to have some fun.”

“Cept when we’re shooting chickens, Sam, eh?” One of them says, raising a laugh.

Before taking up their mugs of tea I see some of them put their cigarettes down on the piano keys.

“Ahh, nice tea luv. U married yet?”

“In a few months.” I said, and with my heart beating fast I turned stiffly and left them to my father and brothers.

When I came in with fresh tea the cigarette butts had burned out on the ivory keys. I wanted to cry seeing the piano I played on, practiced my church music on, desecrated.

**

“There now!” says Dorothy in conclusion, pointing to the heavy brown stains on the keys.

“That’s what they left behind. Weren’t they the terrible blackguards?”

My eyes are fixed on the cigarette burns. A log crackles in the hearth. The wind rises suddenly, growling in the chimney as a gust passes, and then settles.

Ends

Note

For an informative article on the Black and Tans and historical the context see Diarmaid Ferriter’s Irish Times, 7th Jan 2020, Black and Tans: “Half-drunk, whole-mad and” and one-fifth Irish. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/black-and-tans-half-drunk-whole-mad-and-one-fifth-irish-1.4113220