It’s the early 1800s. Imagine an elderly Irishman travelling the country’s rough roads, his horse and saddlebags, like himself under his broad-brimmed hat, wet through from the constant rain, each heavy step of his horse taking him closer to market day, where he expected violent opposition to his fiery evangelical preaching, delivered in Irish and from horseback; if he was lucky, a few converts at the end of the day.

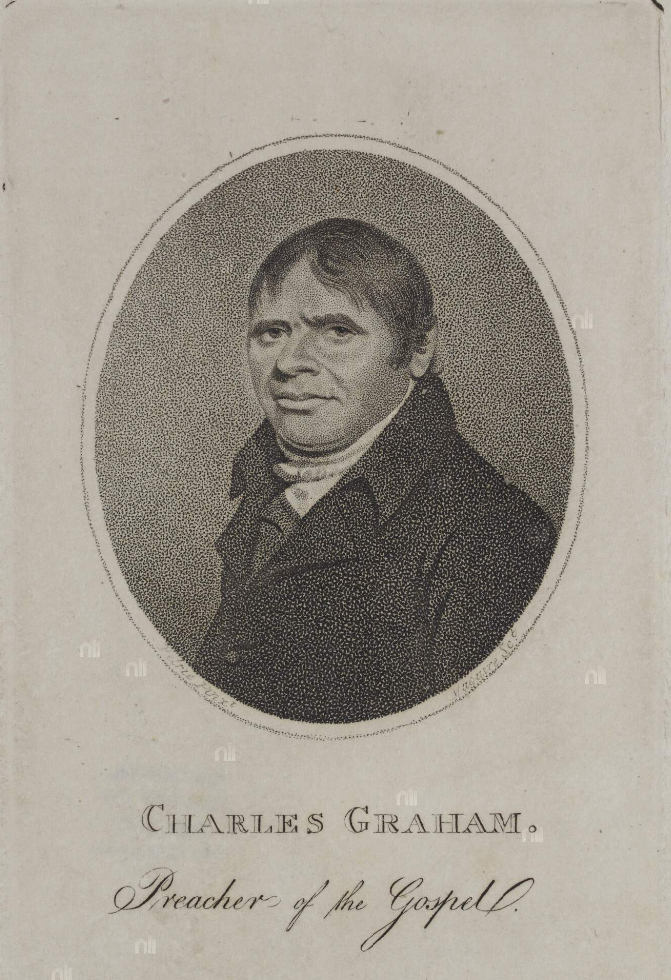

Charles Graham, attributed to Patrick Maguire, (fl. 1783-1820), after an original painting by James Petrie, (1750-1819), held at National Library of Ireland, Dublin.

Such was the life of Charles Graham. He was born near Sligo town in 1750. As a young lad, he laboured with his father on their small farm. Though he had no great education, he could read and write and spoke the languages of the day, Irish and English. During his teenage years he ‘ran with the Sligo bucks’ carousing and causing general mischief. When he was twenty, he was converted, or ‘restored’, when a Methodist friend and preacher challenged his sinful ways. Charles liked the simplicity of the Methodists, with their three rules of ‘no curling of the hair, no gold and no gay clothes’. He said his heart was filled with a ‘holy fire’ and he appeared to have been set on the path of evangelising.

After preaching around Sligo for many years, and at the age of forty, the Methodist Church asked Charles to embark on a wider mission that would take him away from his home for the rest of his life. As a fluent Irish speaker, he had been sought out to further the Methodist’s mission. And so, with his wife’s encouragement, he embarked on an itinerant evangelical journey. He often worked alone and was challenged to build new religious communities among a population that was deeply suspicious of his intent. He was drawn by a crowd, on the street or outside churches, where he proclaimed his hellfire message. Success was measured in new converts; the blacker the sinner the sweeter the victory, he believed.

In 1790, he took up his Church’s request to go to Kerry, which they believed to be a wild and lawless place. His wife and two children travelled with him as far as Limerick while Charles rode on across the mountains into Kerry. He took lodgings in a small hotel in Tralee but word soon reached the local priest of the evangelist’s arrival. The priest, together with a crowd, forced him out, proclaiming him as a ‘false prophet’. Charles found safety in the house of a Protestant farmer outside the town. He spent two years travelling around the county meeting considerable hostility. The Methodists said that his ‘defiance to Romanish opposition was tested in Kerry’ earning him the title of the ‘Apostle of Kerry’. Charles was moved to Fermanagh, Birr, then Longford, Leitrim, South Ulster, Wexford, and finally to Offaly and Westmeath, settling with his family in Athlone.

In 1821, at the age of 71 Charles was still preaching, most of it in the open air. Despite the inclement weather, he seemed to enjoy the atmosphere and challenge of markets and fairs. At the large Enniscorthy pre-Christmas market that year, his hellfire preaching, embellished with many bible quotes, enflamed the crowd who pelted him with anything that came to hand. His journal says that there was uproar and that the town Mayor finally managed to stop the violence. The ‘Romanist incident’, as it was reported, had a positive impact ‘in stirring up ignorant Protestants, lukewarm Methodists and backsliding sinners.’ After his sojourn in Wexford, and in failing health, he moved to Athlone to be with his family, and it was there that he died in 1823 at the age 74.

Title page of ‘The Apostle of Kerry’

This story is gleaned from ‘The Apostle of Kerry, the life of the Rev. Charles Graham’ written by his relative William Graham Campbell and published in 1868. The book is evangelical in sentiment and intention and is still available today from religious publishers. The era was one of waves of revivalist movements that swept the Protestant communities across the New and Old World from 1730 onwards. And the Methodist evangelizing in Ireland, initially led by John Wesley, was part of this phenomenon. The most notable in Ireland was the Ulster Revival in the 1850s, still a touchstone for modern-day evangelicals; it brought many converts to the Presbyterian church, particularly in east Ulster. (See previous blog, ‘The Ulster Revival’.)

It’s difficult to know what Charles was like from this religiously focused book. His son, friends and colleagues spoke kindly of him. After his death, as you would expect, there was much praise from the Irish and the wider Methodist community for his resolute religious conviction and unstinting missionary work. St Patrick’s mission is mentioned as if a Methodist one. Charles’s son, also Charles, wrote of his father’s great meekness, and examples of him turning the other cheek when physically attacked were recalled. And there was praise for his preaching in the Gaelic language with ‘commanding sweetness and fluency with which he spoke the Irish language to his benighted countrymen’.

However, my lasting image of Charles Graham is of a man fired by a singular vision of life, death and salvation. A man riding Ireland’s lonely roads for some fifty years, towards another town where opposition awaited, suffering the varagies of the weather, until finally, he could neither travel nor preach any more.

The book is a hard read in the modern era, imbued as it is with a sense of colonial entitlement and condescension, the latter towards the oft-repeated, ‘benighted country’ – the majority of the Roman Catholic population and other sinners. It is based on Charles’s journals and his many letters, yet it offers no commentary or opinion on Ireland at that time. There is no mention of the harsh Penal Laws which cemented the hegemony of the Protestant Ascendancy nor of the widespread dire poverty alongside agricultural exports from the Irish estates to England; nor the resulting terrible famines of the early 1740s and the 1840s which bookend the period of the story. The 1798 rebellion gets scant mention other than the account of a Methodist minister being imprisoned and shortly afterwards released in Wexford as ‘a good man’; and the difficult and dangerous travelling conditions during the rebellion and its repression. The Methodists were Dissenters, and this lack of sympathetic comment is surprising given their initial tacit support for the aims of the rebellion.

When a reader highlighted the book to me, my initial interest was drawn to the likely influence that the book had on a younger Charles Graham born one hundred years later in Knockalass in County Sligo. He was featured in a recent blog, ‘The side saddle and other clues’, and had an unfulfilled ambition to be a preacher, though he did become a political campaigner. The two men are believed to have been related. However, as I browsed the book for this story, it was the character of ‘The Apostle of Kerry’ that rode out from between the lines.

End

Print and pdf version here.